As buzz begins to build for the release of former First Lady Michelle Obama’s next book, The Light We Carry, a unique summer program inspired by her first book, Becoming, celebrates its first cohort.

The inaugural Black Girls Becoming Summer Research Institute was held at Vanderbilt University on June 5-17, 2022, and hosted 19 rising seventh- and eighth-grade girls from metro Nashville and as far away as Memphis for a no-cost, residential learning experience. The girls learned more about themselves and their peers through classes in science research, critical consciousness, the arts (visual, physical, and abstract) and financial literacy. It is the first research and enrichment program of its kind that is centered on understanding the impacts, both positive and negative, on Black students and toward advancing the life outcomes of Black girls in society. The participants were admitted through a competitive process that drew 55 applicants for just 20 spots.

“I realized very quickly that this was big work that could reset what it means to be a Black girl in American society,” says Nauff Zakaria, program manager of Black Girls Becoming and a fifth-year doctoral candidate in Hebrew Bible at the Graduate Department of Religion.

The program is part of a $200,000 Trans-Institutional Program grant awarded in 2018 to develop the Vanderbilt Community Lab for the Intersectional Study of Black Women and Girls in Society. The IBWGS draws upon research from sociology, law, STEM, education, African American and Diaspora Studies, divinity, and public health to create an interdisciplinary hub of research, discovery, and teaching activities centered on elevating and understanding structural barriers and forms of resilience Black women and girls experience across various social contexts in society, and how intersectional interventions might be created to expand opportunities and increase pathways to success.

Inviting four Black women scientists to engage these girls in scientific thinking was transformative because the girls just don’t see this at their schools. -Nicole M. Joseph, associate professor of mathematics and science education

The principal investigator for the grant is Nicole M. Joseph, an associate professor of mathematics and science education in the Department of Teaching and Learning at the Vanderbilt’s Peabody College of education and human development. Joseph’s research has shown that Black girls are seldom positioned as knowledge producers in STEM areas. Key to the institute’s curriculum was giving Black girls an opportunity to immerse themselves in an environment of representation and affirmation. Accordingly, all program administrators, instructors, chaperones, teaching assistants, and advisory board members were Black women, most of whom hold graduate degrees or are currently pursuing them.

“Inviting four Black women scientists to engage these girls in scientific thinking was transformative because the girls just don’t see this at their schools,” says Joseph, who also founded the Tennessee March for Black Women in STEM, an annual fall event that seeks to raise awareness about the gendered racism that Black women and girls face in STEM fields.

Centering Black girlhood

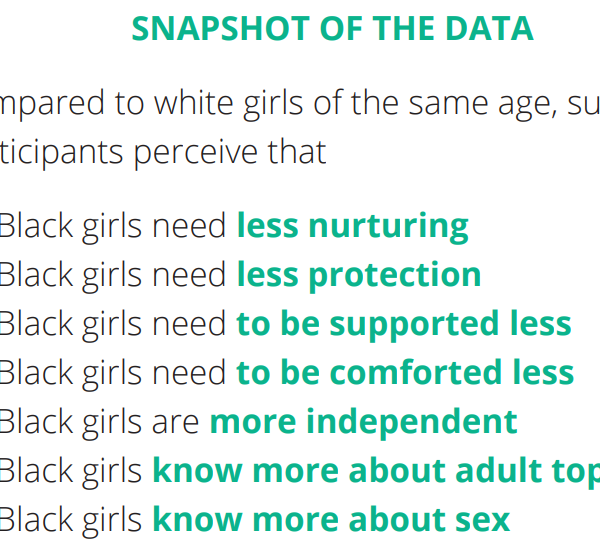

Research shows that formal schooling is often an inhospitable place for Black girls to learn in ways that bring their full humanities to bear because they are often compared to white femininity standards, Joseph explains. Stereotypes held against them include being loud, overly sexual, too talkative, disruptive, and non-intellectual.

In contrast, Black Girls Becoming is a culturally responsive and affirming place “where these girls could bring their genius and be themselves. Their full selves,” she says.

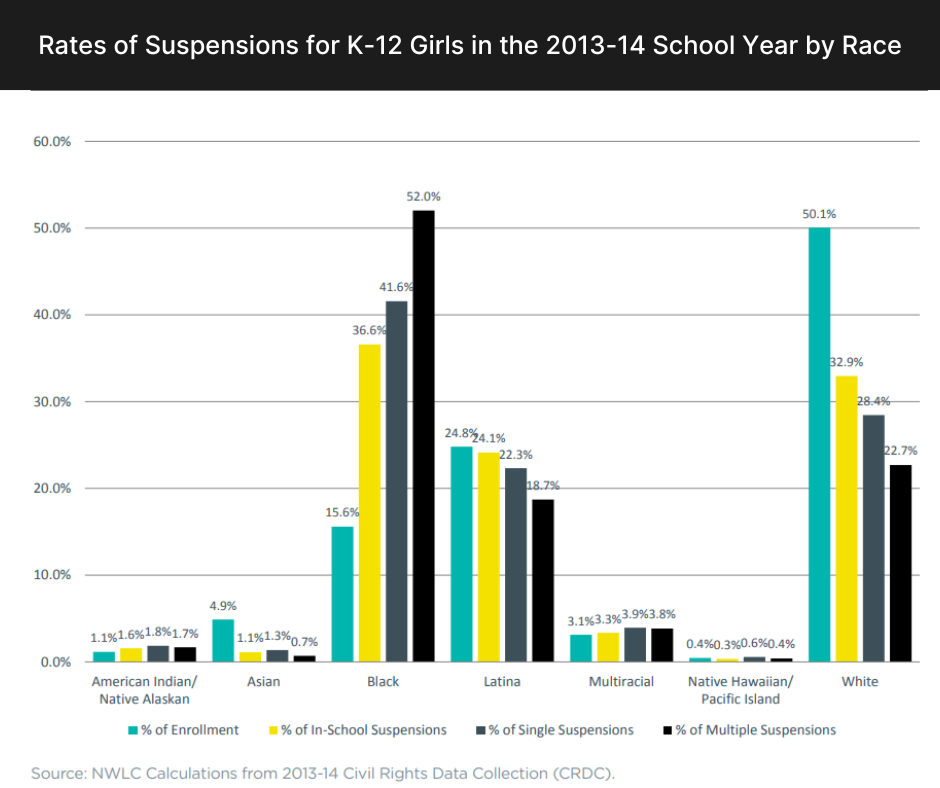

According to Stopping School Pushout for Girls of Color, a report from the National Women’s Law Center, Black girls are 5.5 times more likely to be suspended than white girls, and more likely to receive multiple suspensions than any other gender or race of students. In Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois, Black girls are 8.5 times more likely than white girls to be suspended. In the District of Columbia, where Black girls represent 73 percent of girls enrolled in school but 94 percent of all girls suspended, they are an astounding 17.8 times more likely to be suspended than white girls. This disproportionate discipline starts as early as preschool, with Black girls making up 20 percent of girls enrolled, but 54 percent of girls suspended from preschool.

“With middle schoolers, this is the age group where identity formation is beginning. And being a Black girl brings in so many intersections that are becoming more obvious during that life stage. I say ‘Black girl’ to include women, as well, because every Black woman is healing the Black girl that is inside of them,” says Zakaria, who has taught at the elementary and high school levels, and brought her experience assisting Teresa Smallwood with the Public Theology and Racial Justice Collaborative.

“…every Black woman is healing the Black girl that is inside of them.”

– Nauff Zakaria, fourth-year doctoral candidate in Hebrew Bible

For some girls, this was their first time visiting a university, where they toured the campus, attended their classes on site, ate in the dining halls and slept in the residence halls. The academic curriculum was interspersed with movie nights, vision boarding and screen-free fun. Starting each day with morning centering to help them to get in tune with their bodies and minds, the girls spent two weeks learning about the fundamentals of scientific research in on-campus laboratories, understanding basic financial management, becoming more aware of their agency through critical consciousness and activism, and expressing themselves and exploring their creativity in a culminating “art explosion” on their last day.

“Knowing your craft is just as much of a science as some of the equations they were learning,” says Amina McIntyre, a fourth-year PhD candidate in religion, psychology, and culture, who served as an art and movement instructor for the program. Bringing a background in theater acting and producing, McIntyre also brought in Alicia Haymer as a guest speaker to discuss her experience as a theater director.

Notably, the girls were not restricted from using their personal phones and accessing social media. Rather, breaks to go on social media were built into the schedule. Program instructors noticed that, as the program went on the girls accessed their phones less and less as they acclimated to screen-free activities both in and out of the classroom. After two weeks of spending all their time together, instructors said that they saw shy and timid girls come out of their shells, not only to socialize with each other but also to take leadership positions within their small groups and realize their agency.

Joy without penalty

The Black Girls Becoming program serves as a real-time experiment in intersectional interventions that disrupt the current trajectory of Black girlhood away from negative life outcomes. Data from the program will inform an IRB-approved, nine-year longitudinal study. The study began during the second week and will continue until the girls graduate from high school and, if they choose, pursue higher education. It will demonstrate whether creating an identity-focused STEAM (science, technology, education, arts, and mathematics) curriculum increases the girls’ longitudinal interest and participation in STEAM.

The Black Girls Becoming program serves as a real-time experiment in intersectional interventions that disrupt the current trajectory of Black girlhood away from negative life outcomes. Data from the program will inform an IRB-approved, nine-year longitudinal study. The study began during the second week and will continue until the girls graduate from high school and, if they choose, pursue higher education. It will demonstrate whether creating an identity-focused STEAM (science, technology, education, arts, and mathematics) curriculum increases the girls’ longitudinal interest and participation in STEAM.

“These findings can provide timely information to educators on the importance of incorporating race, gender and disciplinary belonging in STEAM curricula, providing more meaningful educational opportunities for Black girls,” says Kimberlyn Ellis, the research study coordinator for Black Girls Becoming and a third-year PhD student in the graduate program in human genetics. “This study will provide actionable insights to educators, legal guardians, and the girls themselves as they navigate the concurrent developmental trajectories associated with race, girlhood, and STEAM identities.”

The girls were asked to participate in focus groups and surveys as part of Joseph’s TIPs grant-funded research, and all agreed to participate. In one of the surveys, Joseph’s research team found that 100% of girls agreed that they “could be anything they wanted” but showed more ambivalence when asked whether they are “respected and taken seriously in class.” Joseph anticipates that this will improve overtime for the program attendees compared to Black girls the same age who did not attend the program.

“My prediction is that now that they have a few tools, these girls will take more responsibility to speak up to get their academic needs met,” says Joseph, who is the lead editor of Interrogating Whiteness and Relinquishing Power: White Faculty’s Commitment to Racial Consciousness in STEM Classrooms. “I think they will also feel more comfortable bringing more of their authentic selves to the formal academic spaces because for two weeks they celebrated Black girlhood and joy without penalty.”

Stacey Floyd-Thomas, the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Chair in Ethics and Society at Vanderbilt Divinity School, is the parent of program participant, Lillian, a rising eighth grader. She recognized that the program’s interventionist model allowed its participants to become their best selves while learning the hard work that goes into building one’s own character.

“The most vulnerable to invisibility and hopeful in magic are Black girls who are often silenced, shunned and subject to the most pernicious forms of sexism, racism, classism, and ageism in communities and even classrooms that claim to be humane and safe but cannot be trusted to care for them,” Floyd-Thomas says. “They were shown not only that they matter but that becoming their very best is necessary for American society to realize its potential.”

As a participant, Lillian said she met fellow girls who became her “sisters of head, heart and spirit” with whom she was placed front and center in an environment where they were “free to learn, free to be Black girls who laugh out loud, and love the skin we’re in without not having our hair touched or our feelings hurt by the people who find us curious or different.”

The program’s advisory board consists of three Black women faculty from the Vanderbilt Divinity School, including Dean Emilie M. Townes, University Distinguished Professor of Womanist Ethics and Society. “Black Girls Becoming demonstrates the power of a supportive and nurturing environment that allows Black girls to reach deep into their possibilities and have guides who look like them to affirm that if you can imagine it you can become it,” she says. “This is what deep transformation looks like.”

Though this is the last year of the TIPs grant, Joseph is in negotiations with the TIPs Council to expand the research project and make it a line item in Vanderbilt University’s budget. Camilla Benbow, Patricia and Rodes Hart Dean of Education and Human Development at Peabody College, has encouraged Joseph to develop new streams of funding and to pursue a documentary about the Black Girls Becoming program.

“Nicole Joseph has quickly distinguished herself as a scholar and an advocate for Black women and girls in STEM,” says Benbow. “Black Girls Becoming is a powerful example of the kinds of supports that can help these students achieve their fullest potentials.”

To support the Black Girls Becoming Summer Learning Institute, donate to the program (click “Other” and search for Black Girls Becoming) and/or follow them on Instagram.